St. Teresa of Avila:Discalced Carmelites

One of the most remarkable women of all time, Teresa de Ahumada y Cepeda was born on March 28, 1515, probably at the family’s country estate in Gotarrendura near Avila. She was the third child of the second marriage of Don Alonso Sanchez de Cepeda with Dona Beatriz de Ahumada. Grief-stricken at the death of her mother in 1528, Teresa cast herself before a statue of Our Lady and, with many tears and great simplicity, implored Mary to be her mother. When she was sixteen she was placed as a boarder in an Augustinian convent in Avila for about two years to complete her education.

Teresa was a young woman with compelling beauty, warm, witty, and outgoing. She had many suitors, yet on All Soul’s Day in 1535, when she was twenty years old, Teresa secretly left home to enter the monastery of the Incarnation. “When I left my father’s house my distress was so great that I do not think it will be greater when I die,” she later wrote.

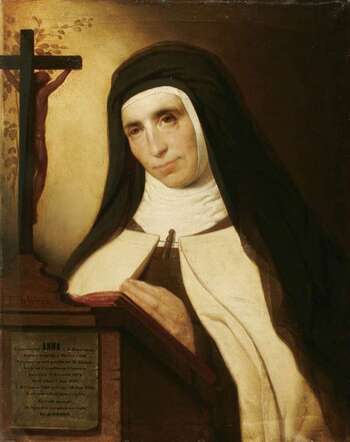

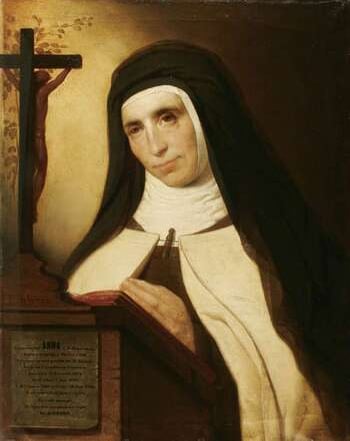

St. Teresa of Avila

St. Teresa's statue of Jesus

A radical change came over Teresa immediately. She no longer spent hours chatting in the parlor, and gave up all concern about her health. Devoting long hours to prayer now, the Lord began to flood her with mystical experiences.

During the ensuing seven years that she lived at the Incarnation, she became increasingly preoccupied with the pressing religious problems of the times: the Protestant Reformation in the north, the breakdown in religious and monastic discipline, and the failure of Carmel to maintain its original ideals.

One day in the fall of 1560 when a group of friends and relatives gathered in Teresa’s cell, the conversation turned to the way of life in the monastery. Half-jokingly, they began to plan “how to reform the rule observed in the monastery…and found after the manner of hermitages, like the original one…which our holy fathers of old founded.” Doña Guiomar, struck by the idea, seriously volunteered to help.

Although nothing definite was decided at that time except “to commend the matter very earnestly to God,” one day in prayer, Teresa received an unmistakably clear order. “The Lord gave me the most explicit command to work for this aim with all my might and made me wonderful promises: that the convent would not fail to be established; that great service would be done to Him in it; that it should be called Saint Joseph’s; that Saint Joseph would watch over us at one door and Our Lady at the other; that Christ would go with us; and that the convent would be a star giving out the most brilliant light.”

Teresa immediately began to seek means to establishing a monastery where the “Primitive” Rule would be observed in all its perfection. It was an enormous task, yet inspired by grace and divinely guided, the stout-hearted nun courageously undertook her first foundation.

St. Teresa of Avila

Yet from the moment she was clothed in the Carmelite habit in 1536, she knew her decision had been the right one. “This new life gave me a joy so great that it has never failed me even to this day.” Teresa’s life at the incarnation was similar to that of the other well-to-do ladies there; however only one year after her profession in 1537, her health broke down, and she left the convent for nearly two years, following various cures which nearly killed her.

Early in her sickness she read Francisco de Osuna’s "Third Spiritual Alphabet" and began to practice mental prayer, sometimes attaining the prayer of quiet and even the prayer of union. Nevertheless, after her recovery—which she attributed to the intercession of St. Joseph—she abandoned the practice of prayer. Although outwardly she continued to lead a devout life, inwardly she had, in fact, compromised. She later admitted herself the she “spent nearly 20 years on that stormy sea…for I had neither any joy in God nor any pleasure in the world. When I was in the midst of worldly pleasure, I was distressed by the remembrance of what I owed to God; when I was with God, I grew restless because of worldly affections. This is so grievous a conflict that I do not know how I managed to endure it for a month, much less for so many years.”

Teresa was thirty-eight years old when she experienced what she called her “conversion.” “It happened that, entering the oratory one day, I saw an image…it represented Christ sorely wounded…I was deeply moved to see Him thus.” Throwing herself down in front of the statue with “floods of tears,” she begged Him to give her strength to serve Him.

St. Joseph's in Avila

After overcoming several formidable obstacles, St. Teresa succeeded in establishing St. Joseph’s in Avila on August 24, 1562. On that day Fr. Gaspar Daza, as representative of the Bishop, received the vows of four women: Antonia de Henao (of the Holy Spirit); Maria de la Paz (of the Cross); Ursula de Revilla (of the Saints); and Maria de Avila (of St. Joseph). He also offered Mass and reserved the Blessed Sacrament.

It was some time later that Teresa herself and four companions from the Incarnation received permission from Bishop de Mendoza to live at St. Joseph’s, to initiate the Divine Office, and to instruct the novices. Teresa appointed Anne Davila prioress and Anne Gomez subprioress; however in early 1563 the Bishop made Teresa prioress. The sisters dropped their family names, and Teresa de Ahumada became Teresa of Jesus. Although Teresa and three companions from the Incarnation had received permission to remain at St. Joseph’s for one year, at the end of this period, Teresa asked permission from the Papal Nuncio to be confirmed by the Provincial, to transfer definitively from the Incarnation to St. Joseph’s.

St. Joseph Monastery in Avila

Teresa makes it quite clear in her writings that at no time up to this point had the thought of renewing the community of the Incarnation entered her head, much less a reform of the whole Order. Her only concern then was to find a little corner where she and a few like-minded friends could pursue a more perfect life of prayer for the Church.

Since solitary prayer was the essence of the life originally adopted on Mount Carmel, St. Teresa chose the modified Rule of St. Albert as the juridical and spiritual charter of her renewal. Referring to it as the “Primitive Rule” or “The Rule of Our Lady of Mount Carmel,” it was this Innocentian Rule that she used as the basis of the Constitutions she wrote for her nuns.

St. Joseph’s in Avila became the first convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns, and was the beginning of a movement which was to give a new Carmelite family to the Church. Discalced literally means “without shoes,” but in religious parlance of the time it indicated an Order which had reformed itself and adopted a more austere life where members either went barefoot or wore open sandals as a sign of poverty.

New Foundations

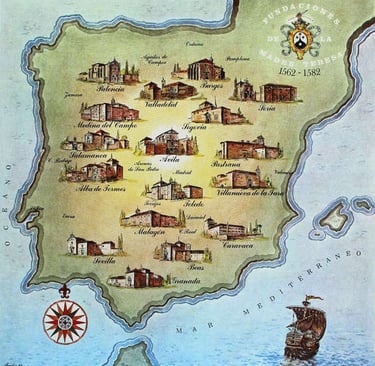

It was Teresa’s original intention to remain at St. Joseph’s the rest of her life, but after only four years—“the most restful years of my life,” she later wrote—she left to make new foundations. Inspired by a visiting Franciscan missionary from the Indies, Alonso Maldonado in 1566, she was later encouraged by the Carmelite Father-General, John Rossi, who visited Avila in 1567. That same year she made a second foundation at Medina del Campo, to be followed before her death by fifteen others.

Monasteries founded by St. Teresa

St. Teresa also had the unique distinction of being the only woman in the history of the Church to renew an Order of men. After receiving permission from Rossi by letter allowing her to establish two monasteries of Discalced friars, she took immediate steps toward this momentous work, and the first Discalced friary was opened at Duruelo in 1568. In the process, Teresa formed a close relationship with another spiritual giant in the history of the Discalced Carmelites.

St. John of the Cross

The first two friars at Duruelo were Fr. Antonio de Heredia (of Jesus) and Fr. Juan de Yepez (St. John of the Cross).

St. John of the Cross occupies a major position not only in Carmelite history but in Christian thought. He and Teresa have both been declared Doctors of the Church, and are considered by many to be its most outstanding writers on mystical theology.

St. John of the Cross

Although St. John of the Cross was a key figure in the reform and did at times occupy important administrative positions, his primary role was to help mold the first generation of Discalced Carmelites, fashioning them to the highest Carmelite ideal. His writings are textbooks of mystical prayer, of intimate union with God, most of them being addressed directly “to the Friars and Nuns of our holy Religious of the Primitive Order of Mount Carmel.”

Evolution of an Order

Even though for nearly a quarter of a century the Carmelite renewal movement found itself involved in a bitter and brutal struggle for survival, by 1581 there were fifteen monasteries of nuns and eleven monasteries of friars, as well as a separate Discalced Province.

On October 4, 1582, at the age of 67, Teresa died in one of her monasteries at Alba de Tormes. St. John of the Cross died nine years later, on December 14, 1591, in a monastery of friars at Ubeda.

St. Teresa's room in Alba de Tormes

In 1587 the Province became a Congregation, with five Provinces and a Vicar General subject to the General of the order. The Discalced Carmelites became completely independent of the parent Order in 1593, with the consent of the General Chapter. Since that time there have existed two distinct Carmelite Orders, the Calced (also known as the Ancient Observance) and the Discalced, each totally independent of the other, each with its own general, its own administration, and its own legislation.

Spread of Teresian Carmels

In 1604, the Discalced Carmelite nuns made their first foundation in France. Madame Barbara Acarie, a Frenchwoman who was later to become Blessed Mary of the Incarnation, had long wanted a Discalced Carmel in her native land. With the support of Princess Catherine of Orleans de Longueville and after two years of negotiations, the general of Spain agreed to send six sisters of the reform to Paris for this new foundation.

Blessed Mary of the Incarnation

Among the group was Blessed Anne of Jesus, one of St. Teresa’s most distinguished daughters. St. John of the Cross had dedicated his Spiritual Canticle to her, and one observer, comparing her to St. Teresa, remarked that she was “in no way inferior in supernatural gifts and in natural gifts had the advantage.” She had served as prioress in a number of monasteries in Spain, and now she would found the Order in France and the Low Countries.

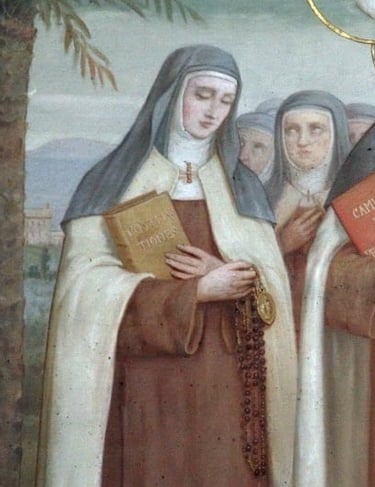

Blessed Anne of Jesus

Blessed Anne of St. Bartholomew, another member of the group, had made her profession as a Discalced Carmelite in the hands of St. Teresa at St. Joseph’s in Avila. She later became Teresa’s personal companion and nurse.

Blessed Anne of St. Bartholomew

Led by Anne of Jesus, the six nuns left Avila on August 29, 1604, and arrived at the outskirts of Paris on October 15. Soon an astonishing number of women applied to the new monastery on the rue Saint Jacques in Paris, and in January of 1605 a second foundation was made at Pontoise by Anne of St. Bartholomew.

Dissatisfied with the situation in France, however, where the nuns were deprived of the direction of Carmelite Friars, in December of 1606 Anne of Jesus led a group to make a foundation in Brussels, Belgium, aided by her friend, the Princess Isabel Clara Eugenia.

Anne of St. Bartholomew remained in France during the early years of the Flemish expansion, but in 1611 she arrived in Mons, Belgium. The following year, she was sent by Anne of Jesus to establish a foundation in Antwerp, Belgium, where she soon became celebrated for her sanctity and unfailing kindness. Even before her death, she was honored in Belgium as a national heroine.

Carmel for Englishwomen

In 1619 Anne of Jesus founded a second monastery in Antwerp for Englishwomen who were unable to lead the religious life in England because of the discriminatory laws against Roman Catholics. Anne selected five nuns for the foundation, two of them Dutch and three English girls who had already made their profession in Flemish Carmels. She nominated Anne of the Ascension (Anne Worsley) as the first prioress. The English Carmel at Antwerp later made two foundations at Lierre and Hoogstraten, and these three houses remained the only English Carmelite monasteries of nuns during the next two centuries. It was only at the end of the 18th century that a group from Hoogstraten departed for the United States, where the first foundation of nuns in the original thirteen colonies was made at Port Tobacco, Maryland.

American Foundation

During the 18th century, by law no convents were allowed in the state of Maryland, and a number of Catholic women had travelled to the Lowlands in order to enter one of the three English-speaking Carmels at Antwerp, Lierre, and Hoogstraten. One of these women was Mother Bernardina Teresa Xavier of St. Joseph (Ann Matthews), who became prioress at Hoogstraten. After the Revolutionary War and the abolishment of the penal laws in Maryland, Mother Bernardina’s brother, Fr. Ignatius Matthews, wrote her: “Now is your time to found in this country, for peace is declared and religion is free.”

The Bishop of Antwerp received enthusiastic permission from Fr. John Caroll, American Prefect Apostolic, and Mother Bernardina was named prioress of the first American Carmel. The initial group included two of her nieces who had entered Hoogstraten in 1783—Aloysia of the Blessed Trinity (Ann Teresa Matthews) and Eleanor of St. Francis Xavier (Susana Matthews). An Englishwoman, Clare Joseph of the Sacred Heart (Frances Dickenson), from the Antwerp Carmel, was appointed subprioress.

On May 1, 1790, the group of four nuns set sail from the small island of Texel off the coast of Holland. They arrived in New York on July 2, where they docked for two days before proceeding to Norfolk, Virginia. From Norfolk a small vessel took them through Chesapeake Bay up the Potomac River to Pope’s Creek in Charles County, Maryland, arriving there on July 10, 1790. The nuns were accompanied on their voyage by Father Charles Neale and Robert Plunkett. Fr. Neale, who had been serving as confessor at the Antwerp Carmel, remained in Maryland with the nuns as their first chaplain, and after the restoration of the Society of Jesus, became the superior of the American Jesuits.

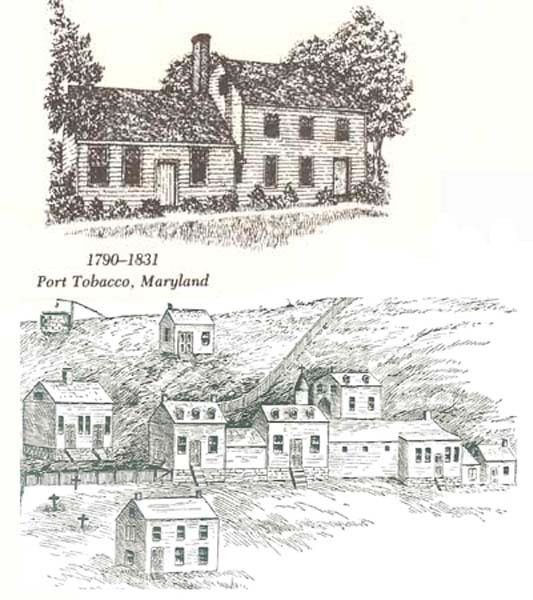

Sketch of the original Port Tobacco Monastery

The nuns first occupied property owned by the Neale family at Chandler’s Hope, but it proved unsuitable. Some weeks later, Fr. Neale obtained another site about four miles from Port Tobacco. On October 15, 1790, the Feast of St. Teresa, the community was canonically established, and the Carmelite nuns began their official existence in the United States. They were the first foundation of nuns in the original thirteen colonies. The new monastery was dedicated to the Sacred Hearts of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Because he was in Europe to receive his episcopal ordination, Fr. Carroll was not present to welcome the nuns to America, but when he returned later in 1790 as Bishop Carroll, he took a great interest in the welfare of the community.

Mother Bernardina continued in office until her death in 1800 when Archbishop Carroll named Sister Clare Joseph as prioress. In the first ten years of its existence, the community had acquired eleven members. In the years that followed, however, the community suffered many hardships. Harassed by lawsuits concerning their property filed by unfriendly neighbors and financially unable to keep up the monastery so that “the rain and snow beat in on all sides,” by 1830 it was finally decided by Archbishop Whitfield that the nuns should move to Baltimore where they might obtain support by the instruction of children.

For more photos, please visit:

Baltimore

In 1830, the monastery at Port Tobacco was transferred to the City of Baltimore, and with an indult of the Holy See, the sisters conducted a girls’ academy next to the cloister for the next twenty years. The prioress, Mother Angela of St. Teresa (Mary Ann Mudd), assigned four nuns to staff the small academy, which was in a building attached to the monastery. By 1851 there were teaching sisters in the archdiocese, and the Carmelites happily terminated their school to return to the Teresian tradition of seclusion.

The great majority of subsequent Carmels in America trace their lineage back to this Baltimore Carmel. Their first foundation was made in St. Louis in 1863, which in turn made a foundation in New Orleans in 1877. The fourth Carmel in America was sent from Baltimore to Boston in 1890, which in turn sent a foundation to Philadelphia in 1902. The sixth monastery was established in 1907 in Brooklyn from Baltimore. Then in 1908 the seventh Carmel in America, the first on the Pacific Coast, was sent from Baltimore to Seattle.

Next Page: