History of the Carmelite Order

One of the most striking physical features of the Holy land is a mountain range in northwest Israel that rises up from the Mediterranean Sea in a bold promontory 560 feet above sea level. The name of this mountain range is Carmel, and it is the birthplace of the Carmelite Order.

The western slope of the mountain faces the sea and is deeply ridged by a series of wadis (valleys containing the bed of a watercourse) running down toward the plain of Sharon. Between two hills of the mountain, there is a perpetual spring flowing from the foot of a rock. “According to tradition,” writes Fr. Marie-Joseph, OCD, “the spring began to flow at the prayer of the holy prophet Elijah.”

St. Elijah

Ruins of the Carmelite Chapel on Mount Carmel

Towards the end of the twelfth century, after the end of the Third Crusade and the return of Latin Christianity to the Holy Land, some western hermits “after the example of that holy man and solitary figure, the prophet Elijah,” came together at the perpetual spring to lead a hermit life on Mount Carmel. The site was ideal. It offered solitude grottoes, water, vegetation for grazing animals and wood for heating. A village, Anne, used to be situated nearby, and today Haifa is within an hour’s walking distance.

Although little is known about these early Latin hermits, they were most likely a voluntary association of laymen who joined together to live a collective life of prayer and penance.

Mount Carmel and the Spirit of Elijah

For the prophets of the Old Testament, Mount Carmel was an object of veneration with a profoundly mystical significance. Its beauty was seen as an image of God’s beauty, and Elijah’s triumph over the prophets of Baal proved that God’s mysterious power dwelt there. The spiritual writers of the early Church came to regard Elijah as the prototype of a contemplative, and this prophet of Carmel has since been associated with the memory of the holy mountain.

At some time between 1206 and 1214, under the leadership of a man traditionally known as Brocard, they asked St. Albert, Patriarch of Jerusalem and Papal Legate to the Holy Land, to provide them with a “formula vitae”—a rule of life.

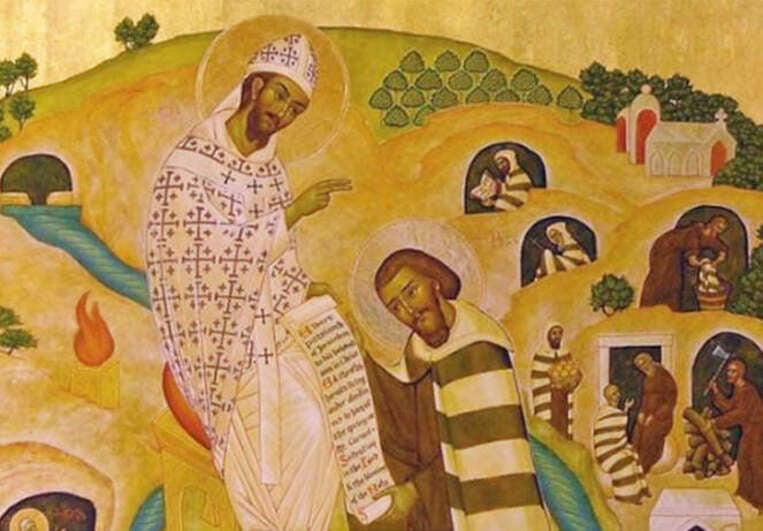

St. Albert of Jerusalem giving the Rule to "Brocard"

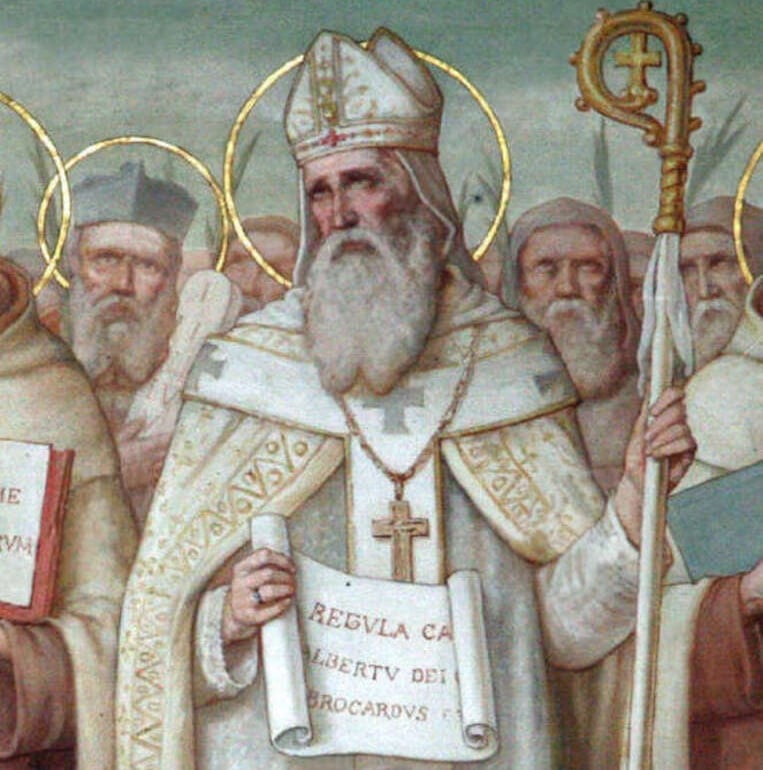

St. Albert, Lawgiver

Descended from a noble Italian family, Albert was a Canon Regular of the Holy Cross and was appointed Bishop of Vercelli in 1185 when he was only thirty-five years old. During his twenty years of service there, he gained a reputation as a diplomat, and after the resignation of Godfrey, Patriarch of Jerusalem, Albert was elected by the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre to take his place.

St. Albert of Jerusalem

Since at that time Jerusalem was under Moslem occupation, he established his residence at Acre, nine miles north of Mount Carmel. He distinguished himself in Palestine, as he had in Europe, both as a diplomat and churchman, and was highly esteemed by Pope Innocent III, who had ratified his election and appointed him Papal Legate.

Primitive Rule of St. Albert

Although this important Church official may have considered it an act of minor importance, the rule that Albert wrote for the group of hermits on Mount Carmel has proved to be his most durable contribution to the life of the Church.

This “Primitive Rule,” as it is commonly known, is a remarkable document in the skillful way in which it synthesizes the potentially conflicting elements of solitary and fraternal life. It is a short document, only about 2,000 words in the original Latin, but beneath its bareness, there is a great depth of spiritual insight. It is made up for the most part of Scriptural texts, thus giving it an unmistakable biblical flavor or perennial hidden beauty.

The rule begins and ends with Christ. Christ is to be the center of Carmelite life and the hermits “to live a life of allegiance to Jesus Christ…unswerving in the service of the Master,” as admonished by St. Paul.

St. Albert of Jerusalem presents the Rule to the hermits on Mount Carmel

The nucleus of Albert’s Rule is solitary prayer. “Each of you is to stay in his own cell or nearby, pondering the Lord’s law day and night and keeping watch at his prayers unless attending to some other duty.” The prayer was to be the Psalter (Book of Psalms) for those who could read; a corresponding number of “Our Fathers” for those who could not. Also, manual work was an essential, both to avoid the perils of idleness and as a means of supporting themselves.

To counterbalance the eremitical elements of his Rule, Albert prescribed that the “brothers” were to meet weekly for spiritual conversation and/or mutual correction. They were to elect a Prior, who was to govern them in a spirit of service and to whom they were to vow obedience as the representative of Christ. Property was to be held in common, the economic structure one of a voluntary commune, with each Brother to receive whatever befitted his age and needs.

Above all, they were to build an oratory where they could come together daily for a common celebration of the Eucharist. The whole pattern of life was structured solely to enable the hermits to give undivided attention to God.

Although specific devotion to Mary was not mentioned in the Rule, the hermits’ first oratory was dedicated to St. Mary, placing their new institute under her patronage and protection and pledging themselves to her service. Thus, in time, they became known as “the hermits of St. Mary of Mount Carmel.”

Although the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 forbade the formation of new foundations, by 1226 Pope Honorius III released the hermits from the edict to adopt either the Benedictine or Augustinian rules and reimposed the Rule of St. Albert on them “for the remission of their sins.” On April 6, 1229, Pope Gregory IX gave the Rule explicit confirmation through his apostolic letter Ex officii nostri.

Statue of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel at St. Joseph's Carmelite Monastery in Seattle

Migration to Europe

In that same year, the position of Christians in the Holy Land began to deteriorate, causing a rapid decline in the flow of pilgrims and the alms given to the hermits on Mount Carmel. During the next ten years, the situation worsened to the point that they made the crucial decision to send some of the brethren to establish new foundations in Europe.

By 1247 there were three or four small provinces in Europe – Cyprus (today unidentifiable), Messina in Sicily, Aylesford and Hulne in England, and Les Aygalades near Marseilles in France.

It soon became clear to the Carmelites that the eremitical life set out in the Rule of St. Albert was inadequate to meet the needs of their new situation. A fundamental modification of the Rule itself was urgent if they hoped to survive in Europe. A General Chapter was summoned at Aylesford for Pentecost of 1247.

Aylesford Priory in Kent, England

The Prior of the hermitage at Mount Carmel was at that time the highest authority of the new Order, and it was most likely he who organized this first General Chapter. During the course of the meeting, the first Constitutions were adopted, a Prior-General elected, and two brothers appointed to humbly petition Pope Innocent IV that the Rule of St. Albert be modified.

Modification of the Rule

Two of the Holy Father’s secretaries, both Dominicans, were appointed to the task; and in October 1247 the Papal Bull Quae honorem was promulgated, perhaps the most significant pontifical document in Carmelite history. Its effect is still felt today. Under this document, foundations were not limited to desert places only; meals were to be taken in a common refectory; the recitation of the canonical office became obligatory; the time of strict silence was confined to a shorter period; and abstinence from meat was dispensed for travelling or begging hermits.

Pope Innocent IV

The essentials of the life were not changed; the door was merely opened for changes which would make the Carmelite way of life more practicable in the new society. This “Innocentian Rule” is to this day the official text of the Carmelite Rule throughout the Order.

Expansion and Decline of the Order

With the adaptation of Innocentian Rule, the Carmelite Order began to thrive in Europe. Within sixty years of its arrival, it grew from the three or four small foundations represented at the Chapter of Aylesford to twelve provinces containing 150 houses. By 1400 that number had doubled, and in the 15th century new provinces were added in Germany, Bohemia, Denmark, and Spain.

Because of the emphasis on urbanization and apostolate which came as a result of the Innocentian Rule, Carmelite life began to develop along more mendicant lines, creating a dramatic struggle within the Order with the defenders of the more contemplative desert tradition, who lamented the “utter passing away” of the order’s original spirit. Abuses within all the mendicant orders were prevalent at this period, as well as a decline in the whole Church, suffered through the weakening and divisive effects of the Black Death, the Great Schism of the West, and the Hundred Years War, all in the 14th century.

Although there were various petitions to the Holy See for further mitigations of the Rule, the history of Carmel over the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries was largely an account of repeated efforts at renewal.

Carmelite Nuns

In the midst of this general decline within the order, there arose a man who was to profoundly affect its destiny and who has become known as the founder of the Carmelite Nuns.

Blessed John Soreth, who served as Father General of the Carmelites for twenty years (1451-1471) was a Frenchman with a firm will, great courage and a saintly quality of humane sensitivity. Through the force of this one man’s personality, the Order was lifted out of the morass of indifference and lassitude into which it had fallen.

Blessed John Soreth

Walking or riding muleback on his incessant trips throughout Europe with his one companion, he was so tanned by the sun that he was called the Ethiopian Devil by his enemies. It was during these travels, ranging from Poland to Sicily, that he became interested in groups of pious women affiliated with the Carmelite Order called Beguines.

These women lived together without vows or official status, wearing a Carmelite habit and following the broad outlines of the Carmelite Rule. Called Beatas in Spain, Mantellate in Italy, and Humiliates in Lombardy, one such group in Florence petitioned the Carmelite friars in 1452 for admittance to the Order as nuns.

This issue was raised at a provincial chapter at Florence presided over by John Soreth, and apparently at his suggestion, the friars voted to forward the Beguines’ petition directly to the Holy See with a request for permission to establish convents of Carmelite Nuns.

On October 7, 1452, Pope Nicholas V issued the Papal Bull Cum nulla, granting the Carmelite prior general and provincials permission to admit into the Order “pious virgins, widows, Beguines, Mantellate, or others who wear the habit and are under the protection of the order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel,” and the Carmelite Nuns was inaugurated.

The community at Florence was immediately elevated into the first convent of Carmelite nuns by John Soreth, and during the next 25 years there was a rapid growth of Carmelite convents in Europe. He himself wrote many of the constitutions for the new foundations, providing for strict enclosure, prayer, solitude, silence, and penance.

Because of the obscure wording of the Papal Bull and the independent status conferred on these new convents, there was a vast disparity of observance among them. Those in the Lowlands and France, under the influence of John Soreth, followed his ideals of Carmelite life, but in Spain and Italy they continue to live more as groups of Beguines than Carmelite nuns, with little real change in their status.

Monastery of the Incarnation in Avila, Spain

One such group, called Beaterio, was founded in Avila by Doña Elvira Gonzales in 1478 and dedicated to St. Mary of the Incarnation. In 1515 these Beatas were admitted into the Order by the Castilian Carmelite provincial and adopted a more spiritual way of life, while still retaining some of the principal features of a Beaterio.

The convent of the Incarnation grew rapidly. By 1535 it had 140 nuns and had to be moved to a larger building outside the city walls. Under the strain of such large numbers, the Incarnation began to suffer financially, and poverty eventually worked to reduce the spirit of religious fidelity.

Although the level of observance was relatively high among the Carmelite nuns compared to some of the shocking abuses within the Church at this time, there was still need for renewal, both among the friars and the nuns.

On November 2, 1535, a twenty-year old girl entered the convent of the Incarnation. Her name was Teresa de Ahumada y Cepeda, and she was destined to alter the course of the Carmelite Order irrevocably.

Next Page: